Memorabilia of Protests: Reflecting on the Sunflower Movement Archive

Tyng-Ruey Chuang wrote a guest post at the Archive-It blog on Memorabilia of Protests: Reflecting on the Sunflower Movement Archive. The article is re-posted below. The depositar lab participates in the Community Webs program at the Internet Archive to help build digital archives documenting local histories and underrepresented voices.

On the 10th anniversary of the Sunflower Movement, we reflect on the current status of the Sunflower Movement Archive. The Sunflower Movement was a month-long civil protest with tremendous momentum in the Spring of 2014 that, even today, continues to shape Taiwan politics. The movement marked a turning point in Taiwan’s uneasy relation with China—the protest itself was ignited by the pending legislation of an unpopular cross-strait service trade deal.

When the movement was winding down, a few academics from Academia Sinica (the national academy of Taiwan) and other universities reached an agreement with the activists occupying the assembly chamber of Legislative Yuan (Taiwan’s legislature) to acquire the artifacts that would otherwise be left behind once they retreated from the site. The occupied assembly chamber had been doubled as the main theater of the protest, itself decorated with an immersive set of protest banners, posters, art works, as well as (sun)flowers and letters sent in by people supporting the movement. Acts of speech, performance, and confrontation in the chamber were video-streamed to the Internet, even broadcast live on TV news channels.

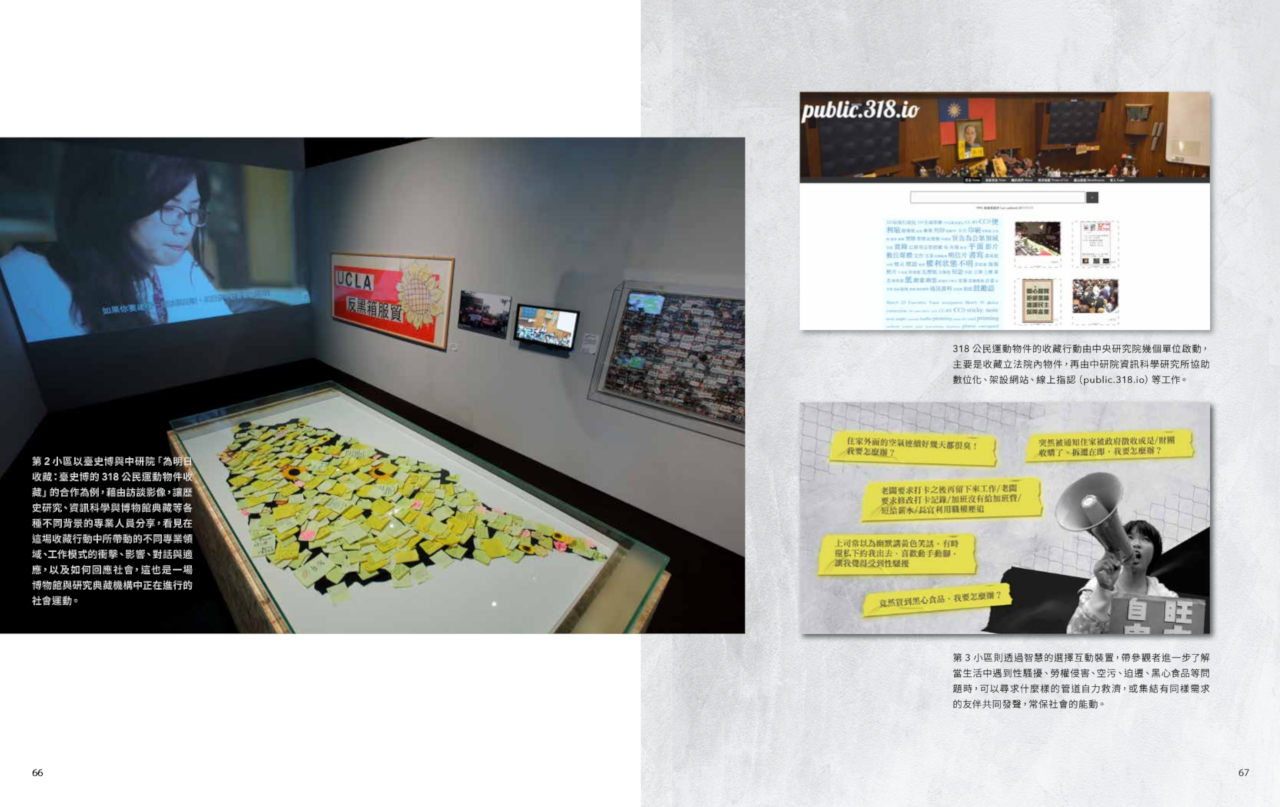

A project team in Academia Sinica was formed soon after to digitize the artifacts systematically collected from the assembly chamber. The team also reached out to those who had been live-streaming events of the movement, and asked for donation of their videos to the archive collection. The Sunflower Movement Archive (thereafter in this article, the Archive) thus includes both digitized artifacts and born digital media (but mostly for those acquired in or around the Legislative Yuan during that time). On March 18, 2015, the first anniversary of the date the protesters broke into the Legislature, the Archive was already online. For the last 9 years, the public has been able to use the Archive to search for images and videos about the movement. This online archive of the Sunflower Movement (318 公民運動文物紀錄典藏庫; public.318.io) is still being maintained by a very small team in Academia Sinica. All physical artifacts and digital media in the Archive collection, however, had been transferred to the National Museum of Taiwan History in November 2016 to become part of the museum’s permanent collection.

Previously we had written about the Archive: How was it being set up and the rationale behind it. The catalog of the collection was soon put online so as to let the public know what had been collected and digitized. In addition, the online catalog allows people to search the Archive and, if they find items of their own, to identify them and to release their high-resolution images to the public to reuse (with a CC license) or to put them into the public domain (with CC0). By upholding accountability and transparency, we aim to establish the Archive as a public resource from which remembrance of the movement can be drawn freely. In the following, we illustrate how the Archive has been used by museums, researchers, and the public to meet their needs. We then reflect on the limitations of the Archive and the challenges it faces.

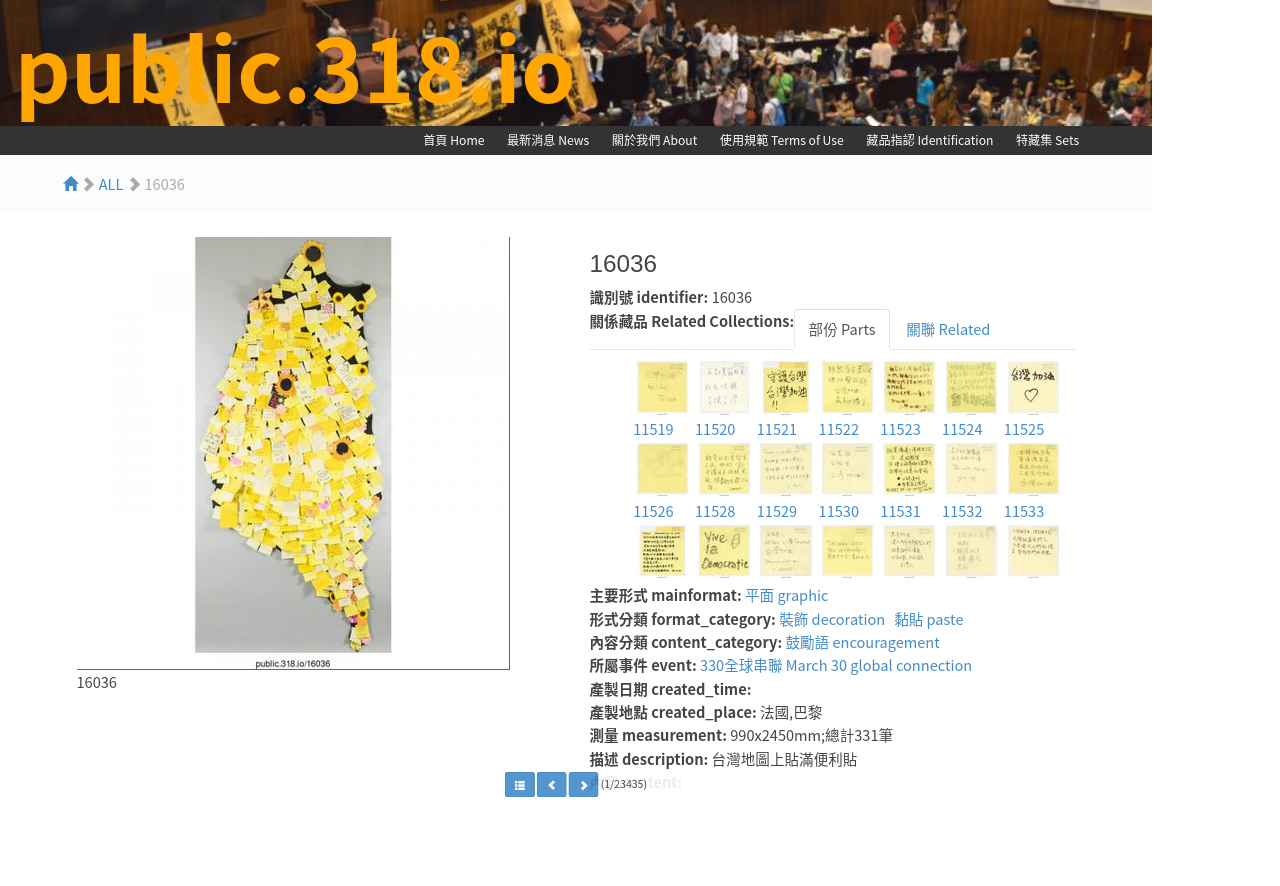

The National Museum of Taiwan History (NMTH) featured the Archive collection in a year-long special exhibition on Social Movements in Post-War Taiwan from May 2019 to May 2020. A large poster in the shape of Taiwan island, itself composed of hundreds of encouraging notes, was shown in the exhibition among others. The poster (Archive no. 16036) originated from supporters of the movement in France. All the hand-written post-it notes had been individually transcribed, hence can be searched by text on the Archive website (see e.g. no. 11524, no. 11544, and no. 11553). The part-whole relation of the notes to the poster has also been kept in the collection so some context is preserved. The Archive collection proves to be a valuable resource for scholars and students researching the movement. Research articles, including a doctoral dissertation, have been written based on materials from the Archive (see e.g. Chen; Ho, Huang and Lin; and Verrall).

With the Archive online and accessible, we started to see critiques and commentaries on the Archive itself and the issues of preserving artifacts from contemporary events as they are unfolding. In retrospect, we realize the many limitations of the Archive. It is the output of an emergent action organized by some academics. The collection is limited in its initial scope and further expansion. It has neither materials from social media nor activist interview. The only major addition to the Archive was the inclusion in late 2020 of about 20,000 photos on the surrounding of Legislative Yuan in the heyday of the movement, painstakingly documented by Yellow Dinosaur (黃恐龍). The Archive was set up with agility, novelty, and public interest in mind. Over the years, the Archive continues to function well in fulfilling its purposes. In the last few months, for example, several film and TV producers contacted the Archive for images and videos to use in news reporting and documentary on the 10th anniversary of the Sunflower Movement.

The outlook of the Archive is not all rosy however. An academic project of this nature is not likely to receive long-lasting institutional support, either curatorial or budgetary, for the persistence of its collections. After all, an archiving project is not the same as a memory institution. We are grateful to NMTH for keeping a copy of the Archive’s digital collection, hence ensuring its permanence. Nevertheless, as individual items being injected and dispersed into NMTH’s own collection system, certain context in the original Archive collection may be lost. This can be seen when comparing the above-mentioned Taiwan-shaped poster in the Archive with the copy in the NMTH collection and its presentation in a downstream website.

We then come down to the crucial question on how better to conserve the entirety of the Archive with its own context. As the information system underneath the Archive is aging fast, there is an urgent need to upgrade the system or to migrate the entire collection to a modern collections management system (e.g. Omeka S). In addition to a planned migration of the entire collection, we want to ensure all the public-facing pages of the current Archive website will be preserved at the Internet Archive (both at the Wayback Machine and via the Community Webs program). The backend database with all the high-resolution media files will be documented, packaged, and preserved as research datasets for future use. The issues of long-term access to collaborative content collections continue to concern us.

In ending, we again emphasize the puny scope of the Sunflower Movement Archive. It includes only those artifacts happened to be collected by a small project team. To research and remember the Sunflower Movement, and Taiwan itself in that juncture in time, all will benefit from diverse, extensive, and accessible sources of archival materials. The Web is still embedded with numerous documentations, memorabilia and stories of the movement. It is saddening only some of them will be preserved before they are lost in time.

(The author thanks Wang-Lin Tseng and Chia-Hsun Ally Wang for their help with this article. The Sunflower Movement Archive is a team project between the Institute of Information Science and the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica.)